Nonno’s Old Box of Memories

Secretly, gingerly, as if uncovering a secret stash of nudie magazines, I dug into the spare bedroom closet. I held my hands high as I stood on my tip-toes. Past the winter coats, past the once-worn wedding party dresses, behind the broken record player. There—finally, there was the box. I brought my Nonno’s old box down gingerly, balancing it on the tips of my fingers as if it were a crystal vase or a hot cookie sheet. Through the clear plastic top, I could make out newspapers and small cloth bags.

I looked at my Italian grandfather’s box. He had served with the 2nd Armored Division, Patton's division, called “Hell on Wheels.” He was a mechanic for the tanks. And now, after 60 years, he had this map in the box which showed everywhere he and his division went. Today I was going to take it from him. After all, he had said I could have it.

I saw a news clipping from the Space Shuttle Challenger tragedy. Then another clipping from the Amazing Day of Snow in Florida. I saw something about the Persian Gulf War. My fingers thumbed through the history, decades of stuff that Nonno had decided was worth saving maybe for somebody to read about someday.

Like digging down through layers of geologic strata, I traveled further back in time as I approached the bottom of the box. Underneath some 8mm family movie tapes, I finally tapped into his relics from WWII. I found his dog tags, then a Nazi armband.

Here, finally, were my Nonno’s relics from the war. He wouldn't really talk about it unless you directly asked him. He might say how cold he was during the Battle of the Bulge. Or how many times he went AWOL during training and made it back to Tampa for a few days with his friends. Not much else.

When I’d asked him what it was like, what the war was like, sometimes he would just stare at me. And for a time, I thought he was just staring at me because he didn’t understand my question.

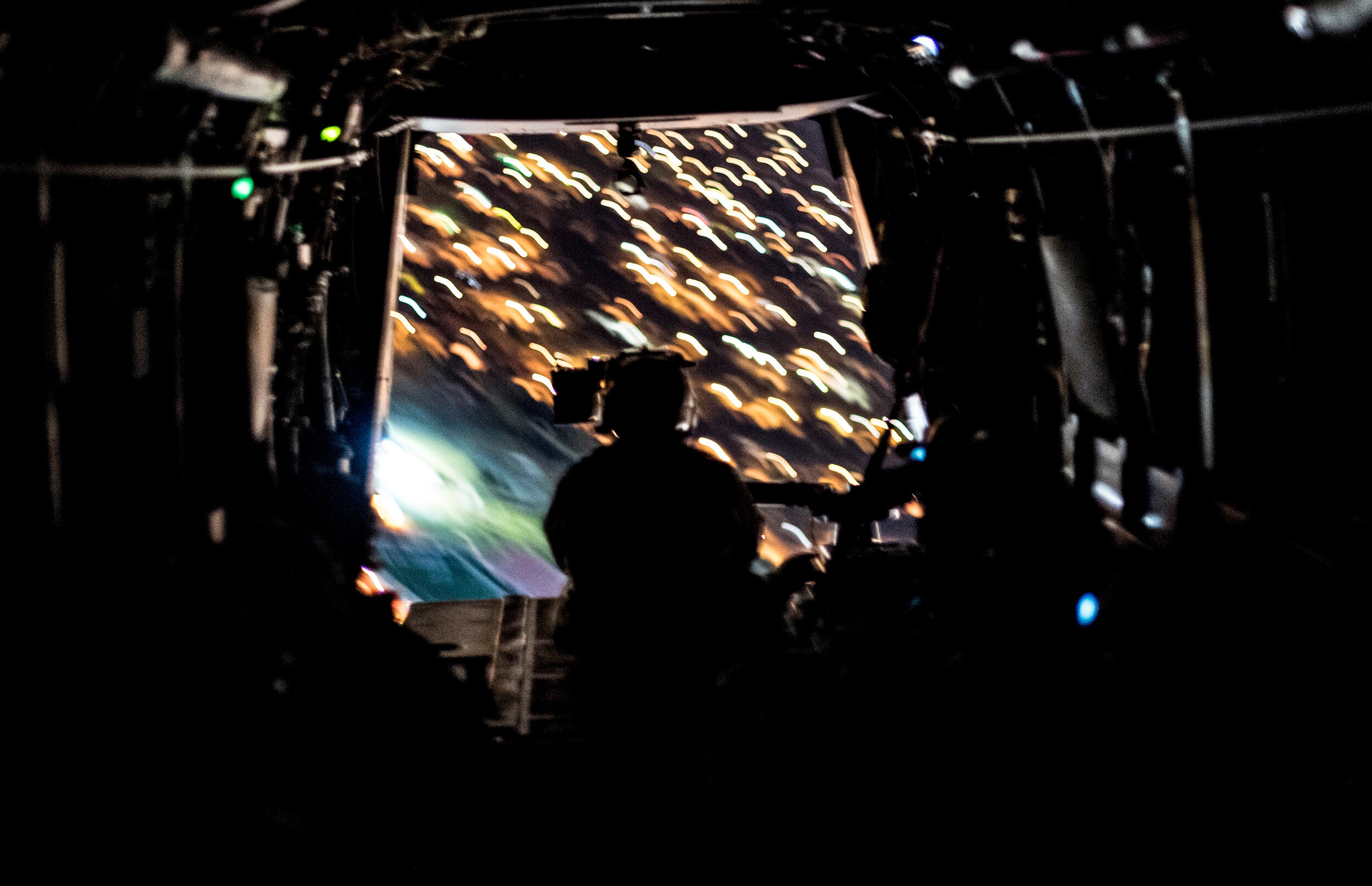

It wasn’t until later—much later, after his death—that I had my own deployments and my own days of seeing dead bodies that I started to understand why he would just stare at me. People would ask me how it was, and my instinctive response would be to say, “How the fuck do you think it was? It was fucking awful.”

I’m glad I never said that out loud, though, because, for the most part, I feel like it’s an innocent question when people ask it. As the immortal Michael Herr said in his book Dispatches, most people aren’t really listening for your answer anyway—they already know what they think about the event and are just asking to be polite.

Nonno was reading the newspaper when I brought the map out—a giant, poster-size, and beautifully colorized chart showing everywhere his division had gone. He looked up when I put it on the table, and he opened his mouth as if to speak.

There was a pause then. A dog barked outside.

“I see you got it,” he said. “That's the map that will show you everywhere I walked through Europe.”

Norfolk, Virginia. Training back in Florida. Waiting, waiting in the Bronx. I traced my finger along the dotted line east across the Atlantic towards Europe. North Africa. Sicily. England, France, Belgium, and then into Germany and the end of the war. Into the past and World History.

Nonno jabbed his finger into the map, silently mouthing the locations. He gave me no details about great battles, or hand grenades, or forced marches. Only, “I got into trouble here. And here. And here.”

He almost forgot one place in France. “Here too.”

“Can you sign it, Nonno?” I asked him. “Can you put your name, and division, and rank? And I'll frame it and put it up in my house.”

Another long pause. I heard the washing machine running.

“What?”

“CAN YOU SIGN IT FOR ME? I'LL PUT IT UP!”

He looked at me like I was stupid. He closed his mouth and narrowed his eyes at me a little. He then looked past me to his wife, Nonni, for a translation.

“The map, Daddy,” she said. “Andy wants you to sign it. Tu firma (your signature). Tu FIRMA.” Now he understood.

“Oh yes,” Nonno replied. “I'll sign it. But I'm not putting my rank; I'm not putting 'Private' in front of my name.”

He then went back to looking at the map. He traced his wrinkled finger over the borders, the bridges, the flags, and oceans. I just stood there with an uncapped Sharpie in my hand.

It had been lunch when I'd first brought the map out. Now my Nonni was boiling milk on the stove for coffee. My wife was stepping through my grandparents’ sunny backyard, picking oranges off of their tree. Nonno was still looking at the map. Now it was my turn to look over at my grandmother, silently asking for an intercession.

“The map, Daddy,” she said. “Tu firma!” Nonno narrowed his eyes at her.

“You know, Nonni,” I said. “It's alright. I don't need the map.”

“Sho,” Nonni said.

‘Sho’ is the Nonni-speak equivalent of 'shut your mouth; you're saying something stupid.'

“He don't need the map,” she went on. “He said you could have it. He just likes to look at it when you get it out of the box.”

Nonno was still looking at it as we talked. I finally decided that taking the map would be something like taking his cat away or his parakeet. I wasn't going to be the one to do it. But my grandmother insisted. So Nonno signed the map right in the middle while looking at his dog tags for the old address he'd had in the Bronx. I would take it the next week and frame it, but I would bring it back as a present immediately after. After explaining that to my wife, she replied, “But you've wanted that map forever! He told you that you could take it!”

“I'll get it later,” I said.

“He told you that you could have it.”

“I'll get it later.”

Years after that, Nonno had passed away. I remember standing at his grave in the Florida National Cemetery in Bushnell, looking out over the woods and white stones at sunset. So many good stories he’d told, and I smiled remembering them--crying because this felt like the end of the story.

I heard his quiet voice, wavering with age, saying how cold he’d been the night of December 31st, 1944. There he was, shivering in France during the Battle of the Bulge. At the time, it didn’t feel much like he was taking his hallowed place in a historic event. It felt mostly like just one more bad time out of many bad times he’d had in the Army.

Blowing on his hands, surrounded by burnt-out tanks and heaps of trash, he couldn’t help but think how everyone back home was probably surrounded by drinks and hot chow. They would be all smiles and dancing at New Year’s Eve parties. A splash of Johnnie Walker Black, ice cubes clinking the sides of the glass. Black velvet outlining a woman’s curves, a small laugh as you trace your fingers down her hand. Smoking cigars on the front steps of El Circulo Cubano (The Cuban Club) in Ybor City, laughing with the boys over one more bullshit story, blowing cigar smoke up into the stars.

Nonno couldn’t be home then, but he was home now. Taking my hand off of his headstone, I spun around in a slow circle, marveling at the way the rows of headstones always seem to line up no matter where you are--reminding me that in the end, everything gets sorted.

It was getting dark, but I felt grateful that, at last, he was surrounded by his brothers and sisters with whom he’d served. Crouching down on one knee, I placed a cigar at the base of his headstone. My wife was waiting for me in the car. Nonno’s map was there in the backseat. It was finally the right time to take it home.

Written By Andrew Schrader

November 2, 2021

Andrew Schrader is a commercial pilot and Urban Search and Rescue (US&R) Structures Specialist. His favorite memory of his Nonno is watching Dick Clark’s New Year’s Rockin’ Eve on TV with him back in Tampa. Every year on that night they would eat pan-fried Italian sausage from Cacciatore & Sons Italian Grocery Store, on top of yellow mustard and Cuban bread from La Segunda Central Bakery. It was a good night.

Reach out to Andrew on Instagram or Facebook @reconresponse or andy@reconresponse.com