War Vets, Fantasy, and a Misunderstanding

* Egregious Nerd Alert * Know Ye that by getting this far you’ve already tread perilously close to where Dungeons & Dragons remains eternally relevant. This week we take a break from current events to talk about something that in 200 years will have undoubtedly outlasted contemporary obsession over protests and pronouns.

The eternal grandeur of our imagination. The desire to learn what is beyond the horizon, being more important than what actually awaits. For many, nothing encapsulates this better than the written works of fantasy fiction.

Fantasy, if anything, is a genre painted with broad brushes. Include some magic, a quasi-medieval Europe setting—good—packaged and it’s ready for the bookshelves. But this realm of both contemporary and classic myth has also been modulated by careful pens; hoping to distinguish one region from the next. And this great country, claiming denizen Cthulhu and Frodo Baggins, make no mistake about it, has been deeply enriched by the minds and makeup of those who’ve been to war.

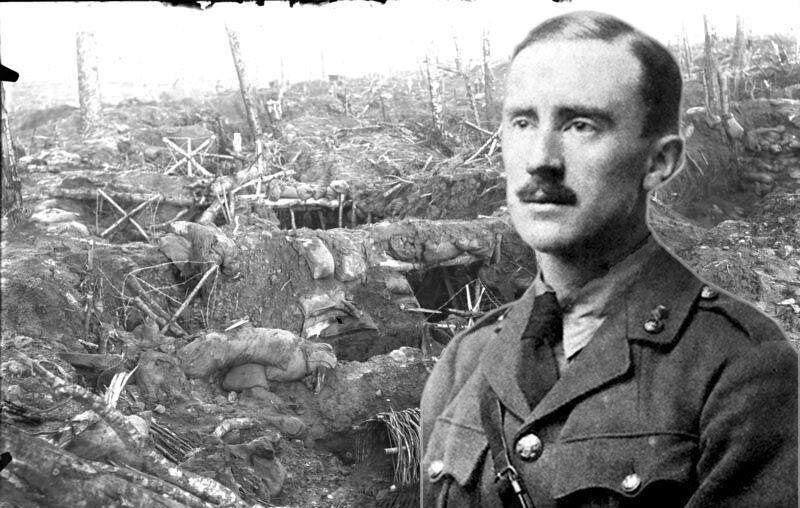

Veterans, both lauded and obscure, have contributed. Men like Roald Dahl, J.R.R. Tolkien, Rod Serling, Ambrose Bierce, and Dennis Wheatley have all either forged genres or served as poetic tour guide into various sub-realms of the dark, high, and the wondrous lowly vineyard known as weird fiction.

It’s important to realize the interplay armed conflicts have always had with literature, but also a modern misconception: people, once pinned “Veteran,” are expected to merely regurgitate historical analyses of ear-shrieking noise or a fetid trench.

This is not so. The veteran mind is often much larger.

There’s no doubt that writers who experience war are later influenced by their memories. Moral dilemmas (or lack thereof) and the environment are good areas to start. But let’s allow for some nuance, and by doing so take the latter example of environment, and this quote:

“In The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, Tolkien speculated that the description of the Dead Marshes may have been based on his personal experience in World War I, specifically, the Battle of the Somme. When it rained, blast craters in no-man’s land would become a series of pools or lakes with bodies of dead soldiers, from both sides, floating in them.”

Pretty convincing, yeah? That the grand master pulled from occurrences in the Great War to craft landscapes in a secondary world. Direct correlation. Direct allegory. Here is the perfect place to address the contemporary misunderstanding.

Notice even Tolkien “speculated” about his own inspiration. Remember also that he was a devout Catholic: two potential sources for him to have drawn from; personal memory and deeply held beliefs. Yet the reverend Robert Murray, a personal friend of Tolkien who was entrusted to proofread The Lord of the Rings, had this to say when asked if Catholicism directly inspired Tolkien’s work:

“No, the values are there all the time because he was that kind of person. But I don’t think the primary intention at any time was to exhibit noble ideals to the world and try to persuade the world to live by them.”

If anyone had reason to do what we so often see today (Look!—someone did something that helps promote meeeee and myyyyy stance) it would be a priest touting Tolkien’s literary success was ultimately due to all that blissful, underlying religion.

But the old reverend didn’t. He abstained—because he knew the man, not just the features someone in 2020 would use to determine what political private thread Tolkien should be excluded from.

By comparing the above, we are able to see three species of inspiration. One, pulled directly, consciously, with deliberate intent to deliver commentary on real-world matters through allegory. The second is pulled directly, unconsciously, as Tolkien seems to believe the Dead Marshes were. And the final being simply resident within a person, rendering their creations as extensions of their deeper makeup little different than genes passed to one’s child.

Noting these differences is important, not only to better understand one’s absorption of the written word, but, in this case, understanding who vets actually are, and seeing clearer their role in benefiting a society post-war. Rarely does the vet get ascribed inspiration from the above second and third.

To perhaps flesh this out a bit better, let’s look at the life of an American, and in a slightly more modern context.

Consider that Rod Serling wasn’t forever wrestling with, of course, PTSD, but rather he was a man, pre-WWII, who was compelled toward adventure, duty, was a seeker, and captor/captive of a certain vision. Such qualities swirled into military service, only to be enhanced by wartime experience, later fermenting and then producing the landmark television show The Twilight Zone.

Anyone who is a fan of the original series will tell you military subjects abound. But now imagine if that show were to debut today. The headline would read something to the tune of Military Veteran Finds Catharsis in Creativity, or Army Vet Examines the Horrors of War in a Quirky New Show.

Wrong. Wrong as it is patronizing.

What draws so many creatives to service is a predisposed needle pointing toward wonder, risk, stratospheric highs and the lows that often accompany them. It is this makeup that pulls them near combat, and it’s this makeup that later, matured and refined, manifests into time-honored creations that have compelled and nurtured our collective imagination.

The greatest credit that can be bestowed on veterans is arguably seen the clearest when manifested in the arts… and then properly understood: vets will always be more than their war before, during, and damn sure after.

October 5, 2020